96% of all mammal life on Earth is either us humans or our livestock. Put another way, all the wild mammals that populate our kids’ storybooks — elephants, giraffes, lions, tigers, polar bears, whales, dolphins, seals, deer, rabbits, kangaroos, koalas, pandas — every last one of their bodies added together is only 4% of the total mass of all mammal bodies on Earth. The rest — 96% — are mostly cows, a whole bunch of humans, and a few sheep and pigs and various beasts of burden.1

It’s been a few years, but I remember exactly where I was standing when I learned this fact (in the dark red bathroom of my little red house), what I was reading (The Guardian online), and the graphic I couldn’t look away from (here, below). I remember the nearly physical impact it had on me. It almost had a sound, which my body still remembers as that darkly metallic yet deep, dull thud you sometimes hear in thriller films: Goozh. It’s all I thought about for days. I felt I couldn’t share it with anyone, because what if they didn’t (or wouldn’t, or couldn’t) get it? What right did I have to impose that horrific knowledge on anyone else, anyway? Or, maybe worse, what if they didn’t really care?

A few years later, I finally get it. We’ve made our planet into one big barnyard. And I think that’s the way we like it, or at least, it’s the only way we can imagine it now. I don’t suppose those who want to terraform Mars are envisioning wild forests or untamed prairies, self-willed and unmanaged by humans. What they plan to build is another big farm, a place to make room for the human overflow of Barnyard Earth.

Americans, especially, seem not to have caught on to the fact that the frontier is closed and that wild places exist only on human sufferance, stripped nearly bare of wildlife, where we allow to multiply only those species that we enjoy hunting. We cull the rest, viciously and often, usually to protect our livestock.2

Wolves in the U.S., for example, having been hunted down to the merest fraction of their former gorgeous abundance, are the subject of constant arguing (by which I mean legal wrangling and Congressional lobbying) about whether or not they should be on the Endangered Species List. There’s a legal definition for endangered, but what it really means is: “species on life support, headed for extinction soon if we don’t make drastic changes.”

It’s a bad sign when your species is up against the line dividing “headed for extinction ASAP” and “rare but not in danger of total extinction right this second,” and all anyone wants to talk about is what side of that line you’re currently on. And of course, you don’t see anyone arguing about whether cows are endangered.

Wolves are unfairly seen as a threat to our livestock, which roam unhindered through much of the so-called “wilderness” we’ve carved out of native ecosystems in this country.3 So wolves get shot and poisoned, and cattle carry on grazing.

Opponents of Endangered Species Act listings dislike the limitations placed on their activities thereby; basically, the law means they have to stop doing things that kill that particular species. Usually, that thing they’re doing is how they make money. And usually, how they make money is some form of agriculture. And here in the West, what they’re typically harvesting is cattle, or in the coastal forests, trees.

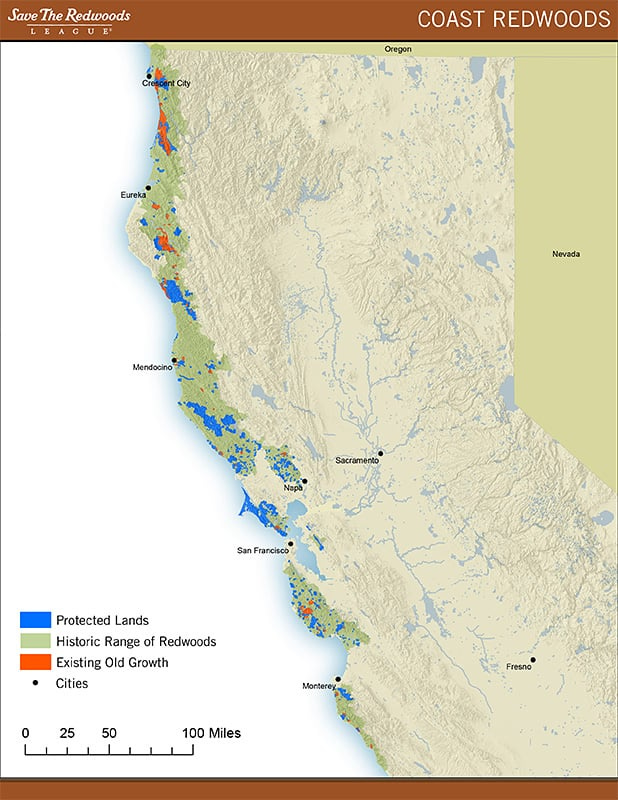

I gave a speech in college about redwood forest conservation that ended with this line: “The fight to save the redwoods is over, and we lost.” (I was one for dramatic endings.) But the underlying reality is this: of the ancient redwood forest that existed in California (and just into Oregon) prior to European contact, just 5% remains (there’s a tiny number again, kind of like that 4% number for wild mammals).4 The rest of the forest has been clearcut at least once, or converted to towns, or plowed into fields. Picture Napa Valley wineries, tree farms, and cute seaside villages now sprawling where towering Sequoia sempervirens had stood since before the Roman Empire was even a thing, in forests themselves older than humanity.5

Imagine walking from the central coast of California, say near Big Sur, 450 miles or so north to what is now the Oregon border, your steps cushioned by millennia-deep, sweetly scented, spongy-soft redwood duff. Imagine the white-gold sun filtering through the canopy in exactly the way the medieval cathedral builders tried to capture the Godlight streaming among massive stone columns. Only, the redwoods did it first, and better.

Imagine picking velvety hot-pink thimbleberries, the sweetest berry you’ve ever tasted, growing from giant nurse logs, food for all comers provided by the dead-but-still-living bodies of fallen trees. Imagine scooping shining salmon from the multitude of little creeks you cross, slow-moving in their spawning, their bodies silvering streams made of fog captured by the magnificent living sculptures rising around them. Imagine following one silver thread down to the ocean, and collecting clams and mussels to your heart’s content, and then imagine walking back up the beach into the forest, full of sparkling light even on the foggiest days, the mothering giants spaced like the pillars of Notre Dame.

Imagine you’re a tiny tawny spotted owl, soaring in silence to feed on bitty reddish voles that never descend to the forest floor, just as your kind have done for millions of years. Imagine you’re a cougar, curled up with your kittens in a living cave hollowed by fire from a colossal tree where you were raised by your mother, and she by her mother, and so on a hundred generations into the past.

Imagine you’re a coho salmon, returning to birth all your children at once in the exact place you were born, having navigated Earth’s magnetic fields in the deep ocean where you’ve lived for years, and scenting the water from your home stream in the uproarious outpourings of coastal rivers. Imagine dying then, feeding your body to the forest that bore you, content that you’ve made your contribution to the million-year stream of salmon lives in salmon streams in salmon forests.

Now imagine instead, slipping in silvery shimmers, having sniffed out your home stream from hundreds of miles away, you’ve navigated there and avoided all the predators who’d like to have eaten you along the way. In one of the wildest of wild green miracles given us by Earth, you somehow got there, you knew you were in the right place, but you couldn’t find your stream. It had dried up because someone cut down the upland redwood forest, and redwood forests make rain from fog, and redwood roots feed streams.6

Or you found your stream but you couldn’t find a way to swim up it. It was clogged with mud because after the humans cut down the forests, the Pacific rains hit as they always do, but there was no soft forest floor and deep-rooted giants to absorb the water, so it all ran off in a flash flood, washing that ancient soil into the ocean, clogging the streams with dead wood and mud. Imagine swimming there at the mouth of your stream in confused circles, over and over till you finally collapsed from exhaustion, the next generation still unborn within your body, rotting together on the beach.

Imagine your big owl eyes see moonlight like humans see the sun. You’re gliding on cool puffs of air, scented with ferns and fronds, your so-soft feathers filtering the air currents so you hardly make a sound. Imagine soaring between 20-foot wide columns, from your nest tree to a starlit emerald grove your ancestors have hunted through ages come and gone, and there’s nothing there. But it was there yesterday, and every day before that since time began. Imagine flying in confused circles over the sunbaked bare soil of the clearcut, then imagine flying back to your sky-high nest, concealed in the wonderworld of tangled limbs at the top of a redwood tree. Imagine you’ve returned empty-clawed, with no meal for your babies.

Imagine next year, you and your mate return to your nest grove, where you’ve raised your children for over a decade, only to find the trees are all gone. Imagine, again, the confused circles, before you and your partner finally fly to another patch of forest, but there are too many refugee owls there, and not enough little fuzzy forest prey to go around, and you are not able to have children that year, or any year after that, because there’s no longer any giant forest to hunt and nest in and you can’t live without that. You ARE, profoundly, that. The giant forest. So when a human spots you in his rifle scope, easy prey because there’s no high canopy to conceal yourself in anymore, well, imagine that.

Finally, imagine these stories repeated up and down the coast of California for a hundred years, a blink of an eye in the life of a redwood, an eternity in the life of a human. The most destructive force ever unleashed on Earth, the European colonizer, swept across California and razed into rubble what might as well have been the Acropolis, the Pyramids of Giza, and Sistine Chapel all in one. (Notice how we always capitalize human creations? I think maybe I’ll start capitalizing Redwood Forest, just to honor an actual Creator, or some such.)

And now tiny scraps of forest cathedral remain to inflict awe on the tourist hordes, and sometimes to bathe solo backcountry hikers in rapturous enlightenment. To remind us what was lost. To remind us what could be again, in a thousand years or so, if we could just. stop. killing things.

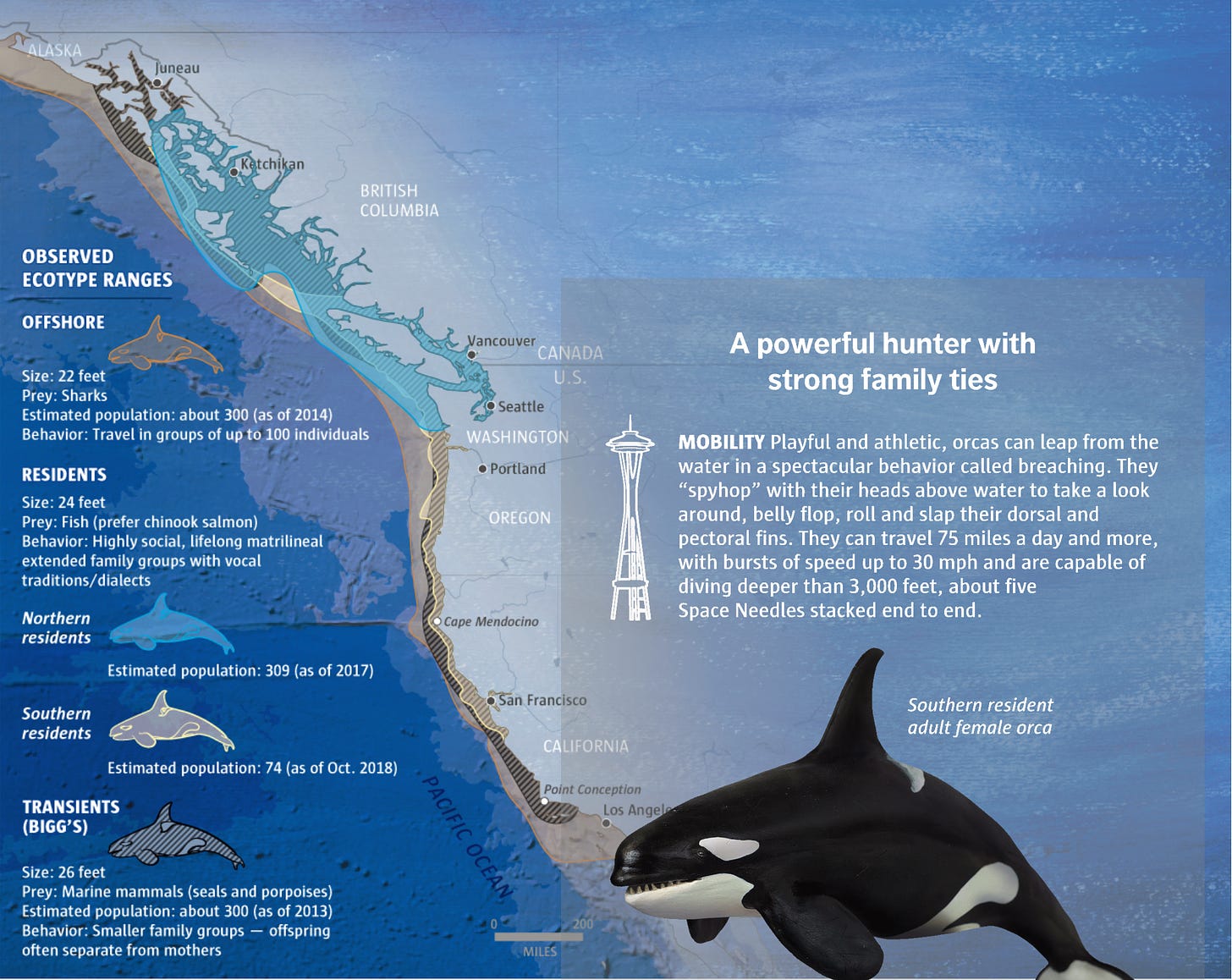

I took a break from writing this to read Caitlin Gibson’s resonant, plaintive tale of Tokitae/Lolita, the orca trapped for nearly her entire life in the Miami Seaquarium. She was born to a tribe of salmon-eating orcas off the coast of Washington, then kidnapped from her mother as a very young girl and kept in a tiny tank until the day of her death over 50 years later.

Tokitae is a Coast Salish name she was later given by a caretaker, and it means something like “Nice day, pretty colors.” Lolita is the name given her by her captors, who forced her to perform for screaming crowds every day despite chronic skin infections and ongoing pain. Lolita means something like … well. It means something.

It is thought her mother might be a 100-year old matriarch, still living free in the wild Pacific. Her presumed mother’s name is Ocean Sun, a name given by her Lummi relatives, a First Nations tribe who consider themselves orca kin.

The Lummi humans fought tirelessly for Tokitae’s return to the waters where her mother and family members still swim. They gave her a new name before her death, Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut, which means simply, “member of this tribe of orcas.” My heart breaks at how their inclusiveness honored her despite her long exile, pimped out to capitalism in a Florida theme park since she was just a little girl.

I can’t stop thinking about the difference between a human culture that would name a young kidnapped beauty Lolita and then force her to perform tricks for a crowd for the rest of her life — and another human culture that would name Tokitae’s mother Ocean Sun and then come together in ceremony to bury Ocean Sun’s daughter beneath the waves after fighting for years to bring her home.

I guess the difference is that one of the cultures would kidnap the tiny human children of the other culture and strip away their names and force them to speak the kidnappers’ language and worship the kidnappers’ god. I guess it’s that same culture that would take carpet bombs in the form of chainsaws to the Redwood Cathedrals. I guess it’s the same culture that shoots owls and wolves for fun. I guess it’s my culture, too, though I don’t belong here anymore.

I’ve been writing of the Redwood Forest of coastal California, but ancient forests and giant trees until recently graced the North American coastline all the way up to Alaska. Credible evidence exists that the Northwest’s native Douglas fir may once have grown taller than the redwoods, perhaps well over 400 feet, and parts of British Columbia are still home to primevally massive hemlocks and spruce.7 These are mostly gone now, of course.

Tokitae’s tribe of salmon-eating orcas, now endangered as well, swims every year from the southern to the northern end of the once-great giant forests of the West, centering their life on the Salish Sea, as blue-green and misty-alive and evergreen-scented a place as you can still find.

I wonder, in their forest-paralleling journeys north to south and south to north along the coast, do they miss the sound of the spotted owl’s four-note hoot floating across the still surface of a bay on a moonlit night? Do they miss the underwater murmurations of fat silvery-red chinook salmon?

I think so because I think that’s — mostly — why they’re endangered: their food is endangered.8 They are slowly starving. The old forests are almost gone, and the salmon are going, and the owl song is pretty much gone, too. Maybe Tokitae’s tribe, too, will be gone soon if we can't change.

A soft rain slips down my roof, and I wonder which drop will eventually pick up the scent of some salmon’s home stream as it spins down a silvery ribbon toward the ocean, calling life home to weave in new threads just as others come to their end. I wonder whether there’s a place for me in that tapestry.

Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R., & Milo, R. (2018). The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(25), 6506-6511.

A good account of this can be found in

’s Harper’s Magazine piece from 2015. Sadly, not much has changed with this federal agency; I recently worked on a lawsuit forcing Wildlife Services to release their field activity records, and the number of wild animals they’ve slaughtered in Oregon alone in the past few years is sickening. Our federal government funds this operation nationwide on behalf of farmers and ranchers. I also recommend Ketcham’s book This Land: How Cowboys, Capitalism, and Corruption are Ruining the American West.The risks posed to livestock by wolves are incredibly overblown: only a tiny, tiny fraction of those that die were killed by wolves. Far and away more livestock are killed by dogs, for example, or weather. See this fantastic interview in The Weekly Anthropocene for more fascinating wolf information.

J.B. MacKinnon, in his wonderful book The Once and Future World, notes that humans have a tendency to eradicate species down to somewhere well below 10% of their former abundance before trying to save the remaining scraps of a population. Of course, that’s not the case for the many species we’ve already extinguished.

Individual redwoods can live 2,200 years, and probably longer. The redwood forests themselves have stood in California for 20 million years.

Gorgeous graphical explainer on the many wonders of the redwoods, including that they make their own rain.

Douglas Fir, Stephen Arno & Carl Fiedler