Trees Live in the Future

…Or they die there.

A few weeks ago, we attended a fundraiser for the Delaware Center for Horticulture that consisted mainly of a silent auction of plants ranging from houseplants to trees. I don’t recall all that we bid on, but I know what we won: two Franklin trees (Franklinia alatamaha), several woodland spiderlilies (Hymenocallis occidentalis var. occidentalis), three river birches (Betula nigra), three fedderbushes (Lyonia lucida), and two loblolly bay trees (Gordonia lasianthus).

All of these plants are native to the eastern United States, but three — Franklin, fedderbush and loblolly bay — are native to the Southeast, not the part of the middle states where Puddock Hill is located. Several were donated by Mt. Cuba Center, which promotes native plants with particular emphasis on the Piedmont physiographic province, which is situated between the Atlantic plain and the Blue Ridge Mountains, stretching diagonally from southern New York to central Alabama. We, too, are in the Piedmont.

I selected these plants for particular reasons. First, because they are all native to our physiographic province and we are committed to natives. Second, to address particular needs in our landscape.

I planted the river birches in the wet woods, where we have much room to fill in, as many trees have died as this woods got wetter over the years due to increased precipitation. Fifteen years ago, we planted the same species, and they have thrived.

The spiderlilies went into the ground in a boggy area in partial sun just north of the small pond, where I hope they will spread. This is one of our first efforts to plant herbaceous species that I hope will establish themselves well enough to compete with invasives. It’s admittedly a small step, but we have to start somewhere.

The Franklin tree (named after Benjamin Franklin) is a rare species no longer present in the wild. It’s a small tree, the flowers of which resemble camelias. Or so I am told; I’ve never seen one in bloom. Last spring, we received a tiny Franklin tree as a gift and I planted it off the barn path, but it didn’t survive the winter. That one went into the ground as a sapling only about a foot tall. The new one is three times that size.

When we renovated our patio a few years ago, we took a lot of trouble to dig up and relocate a stewartia tree that grew near the house. I’m not sure whether that tree is the native or non-native variety, but since its transplantation proved successful and stewartia has similar characteristics to franklinia, I decided with my second attempt to plant the new tree nearby, on the other side of the driveway. The stewartia, however, grows in a sheltered spot by the front of the house. I didn’t have such a location for the franklinia, so we’ll see what happens.

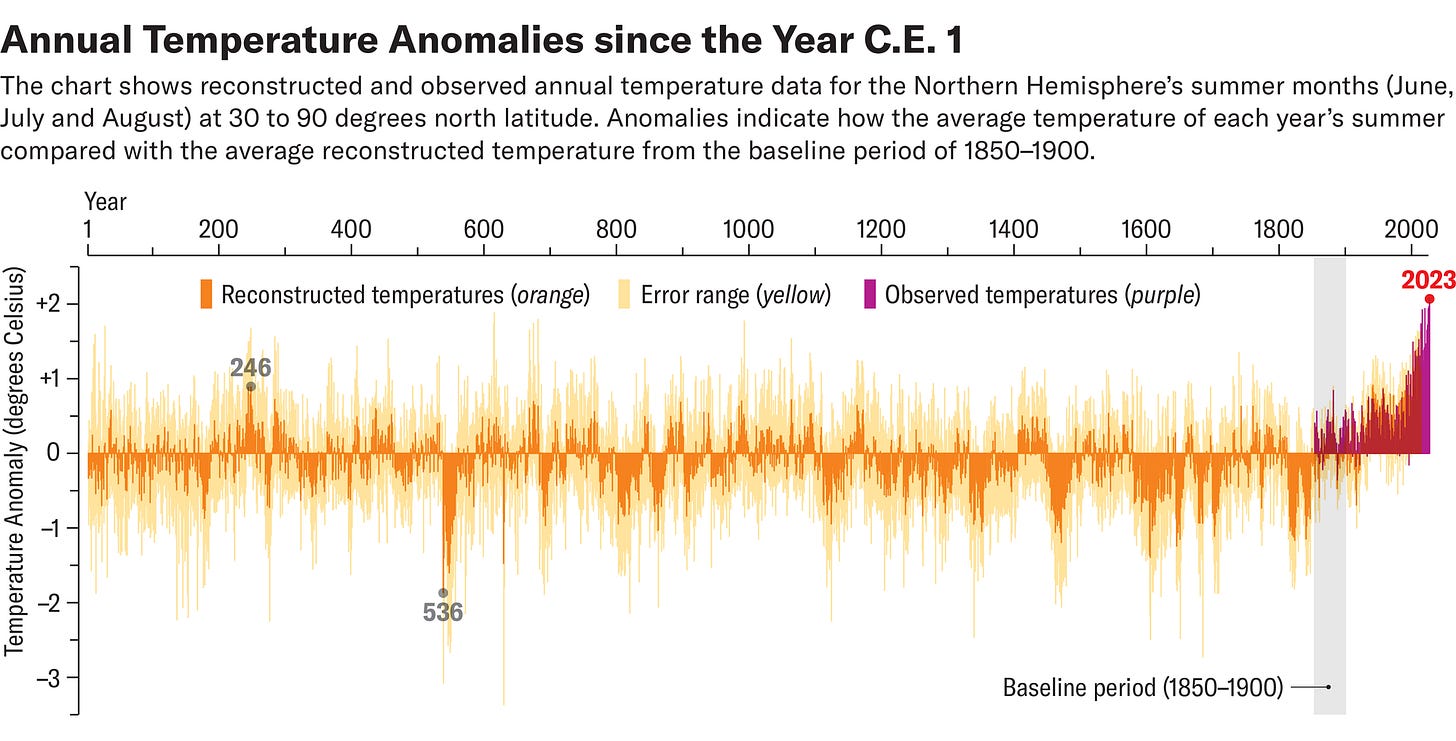

That’s what all gardeners do, right? We put things in the ground and see what happens. One of the big things that’s happening is climate change. Based on tree ring studies, we know that summer 2023 was the hottest in the northern hemisphere in 2000 years:

The Franklin tree is native to the Altamaha River valley in Georgia, a long way from here. Efforts to keep this monotypic genus alive may depend upon introducing it farther north due to warming.

Both the fedderbushes and loblolly bays are at the northern edge of their cold tolerance at Puddock Hill, which is USDA hardiness zone 7a. I planted both in the wet woods.

So half of all we acquired (I might add, very cheaply) goes to a crapshoot. This is appropriate because as a society we have chosen to play craps with our ecology.

I think of a study I read a while ago about the predicted effects of climate change on animal biodiversity in cities entitled “The great urban shift: Climate change is predicted to drive mass species turnover in cities.” Here’s the money quote from the abstract (emphasis mine):

We found evidence of an impending great urban shift where thousands of species will disappear across the selected cities, being replaced by new species, or not replaced at all. Effects were largely species-specific, with the most negatively impacted taxa being amphibians, canines, and loons. These predicted shifts were consistent across scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions, but our results show that the severity of change will be defined by our action or inaction to mitigate climate change. An impending massive shift in urban wildlife will impact the cultural experiences of human residents, the delivery of ecosystem services, and our relationship with nature.

Although it was an animal study, the same can be said for plants, which of course depend upon native animals and vice versa. A paper published this year in New Phytologist predicted that nearly half of angiosperm species (i.e. flowering plants) are potentially threatened with extinction as global heating and its consequences advance. Look out the window. Imagine half of it GONE.

Our great northern hemisphere forests may be particularly vulnerable to a pace of change that nature has rarely if ever seen. A paper entitled “Emerging signals of declining forest resilience under climate change” noted that “Forest ecosystems depend on their capacity to withstand and recover from natural and anthropogenic perturbations (that is, their resilience).” The study of satellite data found that “tropical, arid and temperate forests are experiencing a significant decline in resilience, probably related to increased water limitations and climate variability.”

The study concluded that “Approximately 23% of intact undisturbed forests…have already reached a critical threshold and are experiencing a further degradation in resilience. Together, these signals reveal a widespread decline in the capacity of forests to withstand perturbation…”

Similarly, a study of European forests published in the journal Functional Ecology examined how “climate and tree species composition interact to control the ability of forests to resist and recover from” increased storm disturbance that results from climate change. The study found that “species-rich assemblages had higher recovery and resilience to storm disturbance, while functional diversity improved resistance and recovery.”

What does this mean for the backyard steward?

As modern humans, we are both perpetrators of these changes to nature and potentially their mitigator. If we can fulfill the latter role, we must engage with the reality that nature meant for most trees to grow for a very long time while our planting zones are changing rapidly. Therefore, to promote resilience we must expand the definition of “native” to all zones in our physiographic province, and we should especially introduce trees from nearby warmer climes.

I look out at the great old trees of Puddock Hill and see oaks and sycamores and bald cypresses that have witnessed several human generations. With rapid changes to our environment, there are no guarantees that the species thriving today will live to see our grandchildren and great grandchildren into adulthood.

Trees live in the future — or they die there. To maintain some semblance of the world we inherited from our parents and grandparents, we must push the envelope when planting our own trees.

Spring scenes at Puddock Hill. The big pond:

A path through the barn meadow:

Non-native climbing hydrangea hangs lush on the patio garden arch:

The upper patio garden viewed from the house:

Allium lovers embrace in the raised bed garden:

No-mow surprises include native smooth spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis) in two colors:

And native lyreleaf sage (Salvia lyrata):

My century old oak that hovers over me when I write outside on my terrace, and I are old buddies. We have conversations (sort of).