The Hand of Man

Puddock Hill Journal #70: A reminder that No Mow and Rewilding, as the backyard steward applies them, usually involve human intervention.

When invasive Japanese stiltgrass rushes in like a king tide, as it has recently at Puddock Hill, there’s never enough time in the day. It seems to be everywhere all at once, in beds among perennials and shrubs, at meadow edges in full sun, under trees in the shade—you name it.

There are two ways I know of to fight this scourge without chemicals, and neither is particularly quick on the scale we face. You can pull it up by the roots—which are mercifully shallow—as we do in our planting beds, or you can string trim before it sets seed. The latter strategy requires allowing the stiltgrass to grow tall first, wasting its energy. After it’s knocked back, one hopes it lacks stamina to reproduce. And, as it’s an annual, individual plants won’t come back.

Here’s a caveat. I have been engaged in this battle for the past five years, and the results so far would not yield a ringing endorsement for my strategy. In my defense, stiltgrass seeds stay viable in the ground for five years, maybe longer. Also, certain neighboring properties are not doing their part, and their seeds no doubt blow all over the place. Finally, we never manage to kill it all, no matter how hard we try, and each plant can produce a thousand seeds, according to Penn State Extension.

Despite these facts—or perhaps because of them—I persist in my efforts. Sometimes, as this week, I have to call in the lawn service to do the bulk of the work, string trimming where they can, and mowing where they have to.

One benefit of waiting to do these things until absolutely necessary is that it gives a chance for native competitors to set seed or garner enough energy to withstand being cut back themselves. In among the stiltgrass we find violets, Virginia creeper, white avens, Indian tobacco, and other natives. As great blue lobelia is just coming into bloom, we leave it standing as much as possible and over the past decade have been rewarded with at least a ten-fold increase of this beautiful native, which used to be so rare here that I’d paddle out onto the big pond in a kayak to observe a handful of plants on the untrimmed shore.

Earlier this week, I returned from battle to find a Substack entry among my emails from a sympathetic writer whose work I admire. (We recommend one another’s publications, and there are more than a few subscribers here who came from her direction, for which I’m grateful.) The writer is Lolly Jewett, who concentrates her “biodiversity restoration and sustainable landscape design” efforts around Bethesda, Maryland, and advocates for natives through her publication, "The Bees’ Knees."

This particular edition, entitled “Beware the Brits,” pushed back against three concepts brought to us by our friends across the pond: No Mow May, Plant Hunting, and Rewilding. You can read the piece yourselves at the above link if interested. To summarize her position:

No Mow May often just produces flowers of non-native plants such as dandelions and white clover that mostly feed honeybees, which are not native and in fact compete with our native bees.

Plant Hunting introduces more non-natives to the garden while we should be putting effort toward reintroducing natives.

Rewilding doesn’t work because leaving things completely alone usually invites invasive plants to take over.

So I came into the house covered in the remnants of all the invasives I’d been string trimming only to find that a fellow traveler was criticizing two terms I often toss around. While I’ve never found any need to talk about (or indulge in) Plant Hunting, both No Mow May and Rewilding are relevant to management practices I pursue nearly every day as a backyard steward. It occurred to me that I should consider refining these terms as I use them for my readers.

No Mow

The No Mow May movement did indeed originate in Merry Old England not so long ago. Although I sometimes use the phrase, in practice at Puddock Hill we extend No Mow well past May and far into summer. In my experience over the past few years, dandelions and clover do crop up early, but many natives eventually show themselves—and even sometimes come to dominate. They have included daisy fleabane (Erigeron spp.), brown-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia triloba), deertongue grass (Dichanthelium clandestinum), heal-all (Prunella vulgaris), wild violets (Viola spp.), asters (Asteraceae spp.), Virginia knotweed (Persicaria virginiana), swamp agrimony (Agrimonia gryposepala), and the unjustly unloved horseweed (Erigeron canadensis), among others. As natives, all support our native pollinators while the grasses among them—many non-native but benign—grow tall.

Extending No Mow May through summer in effect produces a young meadow, which you may choose to manage as such or eventually return to lawn.

Rewilding

As it happens, as I was writing this essay another article crossed my feed about a study in Europe that found a quarter of the continent presents a “rewilding opportunity.” The article defined rewilding as “a movement to restore ravaged landscapes to their wilderness before human intervention.”

This definition agrees with Lolly’s, but I use the term in a looser way when advocating for backyard stewardship. In places around the perimeter of the property, I have planted hundreds of trees in somewhat random fashion, as nature would. Some of these trees were purchased. Others arrived on their own in planting beds and lawn and were replanted around the perimeter. Still others—my favorite kind—showed up on their own in situ (wild!) and have been left alone to grow as they may.

To be clear, this isn’t rewilding in the sense of restoring a landscape to wilderness. The “wilds” of Puddock Hill are indeed managed because, as Lolly notes, to leave them completely alone would be to sit helplessly by while invasive plants take over. One of the reasons I favor the string trimmer over the mower is that it allows me to be more surgical when fighting invasive plants, carefully avoiding cutting down native plants I wish to encourage. Call it rewilding with a thumb on the scale, if you will.

The same practice applies to my No Mow efforts, by the way, and the surge of stiltgrass this time of year confirms the point. In spring and early summer, I monitor our No Mow spaces for invasives and attack with the string trimmer when necessary. But when stiltgrass starts asserting itself in mid-August, we gradually increase the mowed area to fight it, even if this means taking down native plants.

Alas, stiltgrass will probably always be with us. Our efforts to eradicate it are as imperfect as the world we’ve created. As Bill McKibben observed in his seminal work, we have promulgated a series of events that have led, in some sense, to “the end of nature.”

The hand of man is everywhere. We brought the stiltgrass here, and we alone have the means to combat it.

A native common Eastern bumblebee samples great blue lobelia flowers in the wet meadow:

Native late boneset (Eupatorium serotinum) prepares to bloom in the tenant house meadow:

Someone’s been enjoying berries from this American pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) growing at the edge of the wet meadow:

Poison fruit hangs from Carolina horsenettle (Solanum carolinense) in the wet meadow:

This perfect non-native daisy shines by the big pond:

The birds won’t be neglecting these elderberries (Sambucus) by the big pond embankment much longer:

Native tall tickseed (Coreopsis tripteris) has moved into the barn meadow:

This native devil’s beggarticks (Bidens frondosa) cropped up in the patio garden. It attracts beneficial insects, so I may leave it be:

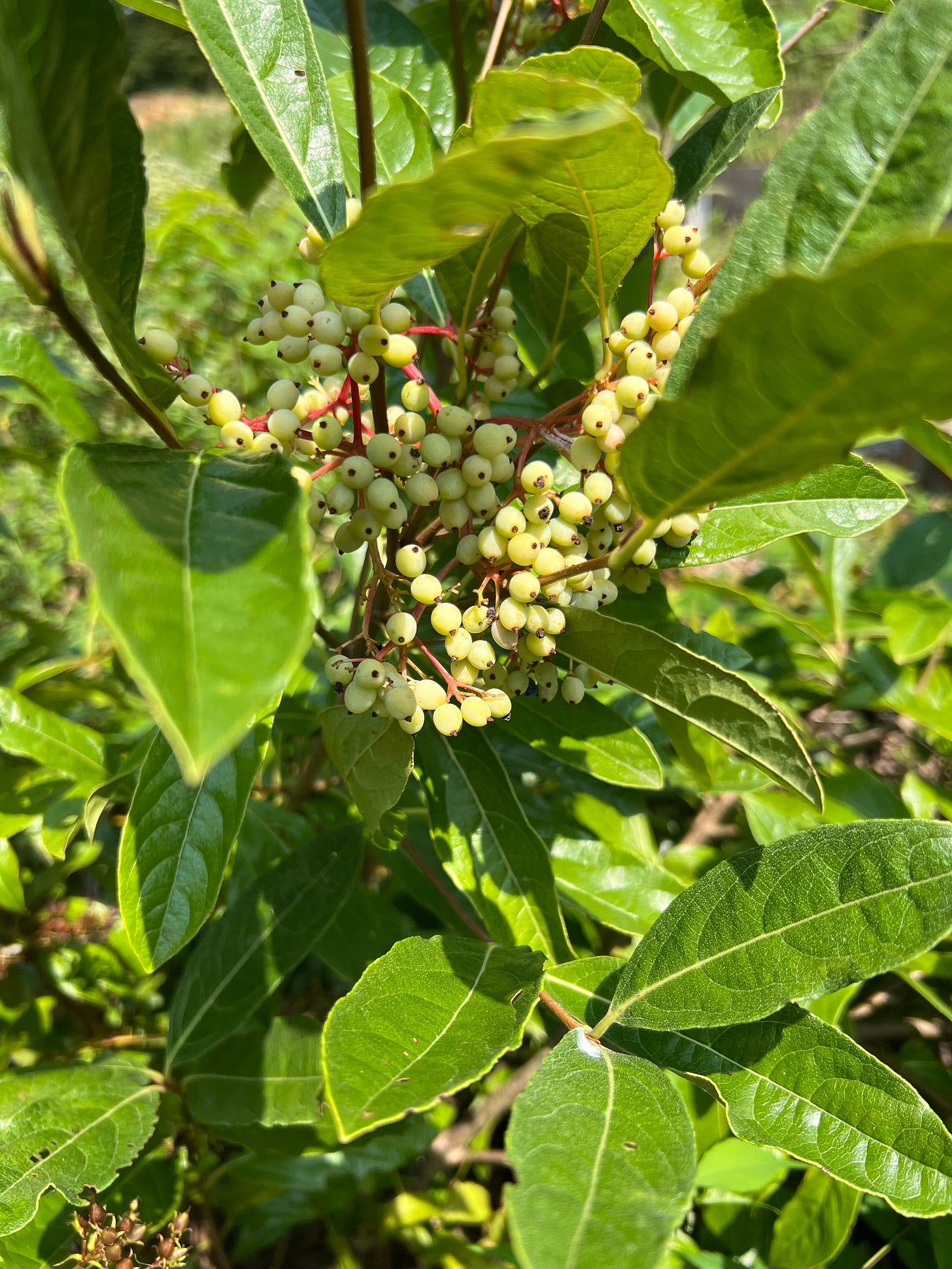

Unripe berries hang heavy on native cultivar Viburnum nudum ‘Brandywine’ in the patio garden:

I agree with you about No Mow May but would also add that the timing (May) was chosen to be appropriate in the English growing season (I have 50 years English gardening behind me before coming to Canada) and perhaps a different month would be more appropriate here - June for where I live, maybe February in some more southerly locations. The other thing is that it's really just a marketing exercise to get people thinking about no-mow every month if possible and it has had moderate success in the regard. Also agree about dandelions.