No Bystanders at the Apocalypse

Puddock Hill Journal #38: The backyard steward can hardly discount what’s happening OUT THERE.

Here is a vista I share often of the big pond at Puddock Hill:

It may appear a bit out of focus, but it isn’t. As in much of the Northeast for the past few days, the sky here hangs heavy with smoke from Canadian wildfires. Even at ground level, we can smell the fug.

There are many things I could write about today at Puddock Hill. I have been meaning to discuss the pickerelweed we’ve planted in the big pond. We were late with the brush hogging and string trimming of certain areas, and the consequences certainly should earn a post. The oak leaf and climbing hydrangeas have begun to flower. Welcome native bumblebees buzz in profusion around the penstemon. Pollinators also cover the Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica), which recently bloomed.

In fact, I posted a video about the sweetspire on YouTube yesterday with only a nod to the smoke in the air. I hope you will visit this new Backyard Stewardship channel here and subscribe! Check out my introductory video from Monday:

But today a thousand projects and local triumphs seem small in relation to the signals we’re receiving from the biosphere. We don’t live in a terrarium at Puddock Hill. We can’t glass out the world.

I confess that sometimes I sit around daydreaming about all the good I think we’re doing on our sixteen acres. I picture the amphibians multiplying in response to sustainable management of the ponds. I imagine native bees and birds thriving in defiance of trends, a fantasy that requires pretending these animals never leave our benign embrace. And I celebrate all the additional shade and attendant benefits that will result from the trees we’ve planted—cooling, slowing erosion, filtering water, feeding wildlife, and—yes—storing carbon.

All of this ignores the fact that what happens beyond our property line doesn’t stay beyond our property line.

We had a mild winter in this part of Pennsylvania. I don’t know yet whether or how much this will contribute to the survival of invasive insects such as stinkbug and spotted lanternfly, but I do believe it explains a certain amount of vigor among invasive plants, which I lamented last week. Many invasive plants leaf out earlier than their native counterparts, lending them an advantage, and a mild winter could give them an even greater head start.

Last year, premature spring warming followed by a late freeze caused our magnolia to lose its buds. Similar false springs can and have caused native flowers to bloom prematurely, before the insects that rely on them have hatched. Fewer insects, of course, means fewer birds.

While we can’t directly attribute any given mild winter or false spring to climate change, higher concentrations of greenhouse gases make these events more likely, and in general winters are warming faster than summers. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration just reported that carbon dioxide levels have hit 424 parts per millions, the fourth-largest increase since measurements began, 50 percent higher than they were at the start of the industrial era, and “continuing a steady climb further into territory not seen for millions of years,” among other distressing superlatives.

The same caveats of attribution apply to the “flash drought” we’re having in Eastern Pennsylvania, but the facts of the moment speak volumes. The historical average precipitation for May in our area is about three and a half inches. We received less than a quarter inch last month, and despite a recent welcome downpour we remain in severe deficit. Before that rain, Larry, our part-time helper, towed a water tank out to many of our young trees. Earlier spring rains made these trees lush, but some had begun showing signs of stress, and any coming spikes in heat might do irreparable harm.

Incidentally, one bit of luck for the trees so far has been relatively cool weather the past few weeks, the result of the same unusual weather pattern that’s driving Canadian smoke this far south. The jet stream, the edge of which generally carries the most moisture, has dipped far below us, likely due to a breakdown in the Arctic polar vortex caused by warming there.

Why are the forests of Eastern Canada burning? We know that drought and premature heat are major factors, and the U.N., echoing scientists, has warned of increasing wildfire incidence and intensity brought on by climate change for precisely these reasons.

In short, the consequences of using the atmosphere as an open sewer for the release of greenhouse gases are beginning to manifest, and while the only moral choice is to continue doing the right thing—indeed, to double down on doing the right thing and urging others to do the same—none of us will be immune to the trouble already baked into the cake. The future was always uncertain, but we have made it more so; we have set Earth’s systems wobbling.

Will drought one day kill the native trees and plants we’re so vested in at Puddock Hill? I don’t know. Will wildfires one day erupt in our area? I don’t know. Will conditions favor invasive species even more than usual? I don’t know. Conversely, will we have too much water, causing root rot and washing plants and soil away? I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. But I do know that the biosphere is screaming in rage, and Mother Nature’s response will spare none of us.

Here are a few observations made over the past few days.

From Brad Johnson’s Hill Heat:

“None of the existing monetized economic costs of climate change — like when we come up with the social cost of carbon or any of that stuff,” climate scientist Marshall Burke notes, “wildfires are not in there at all.”

From Eric Levitz in NY Magazine:

Critically, the economic consequences of wildfire smoke extend beyond their direct medical impacts, as people lose time, money, and quality of life to preparing for heavy smoke days, mitigating their effects, canceling plans, and accommodating their impaired health.

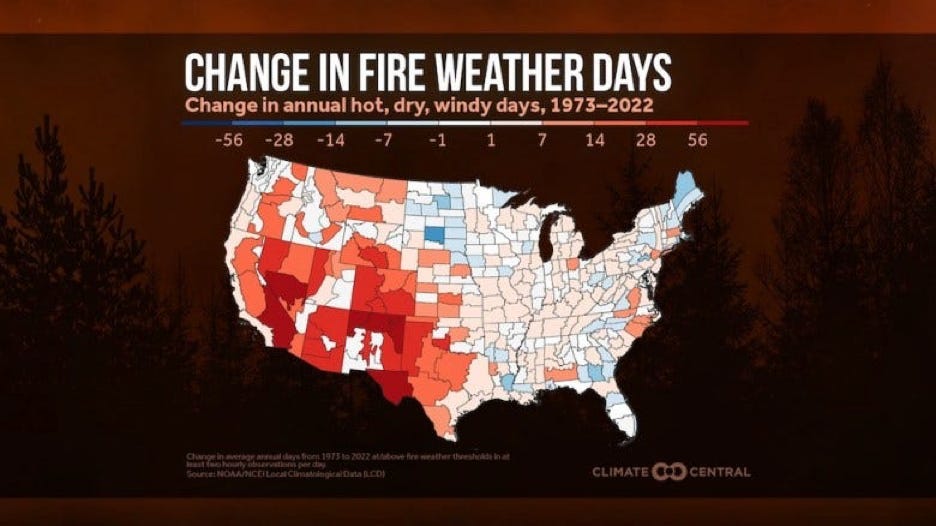

Bill McKibben in The Crucial Years (graphic from Climate Central):

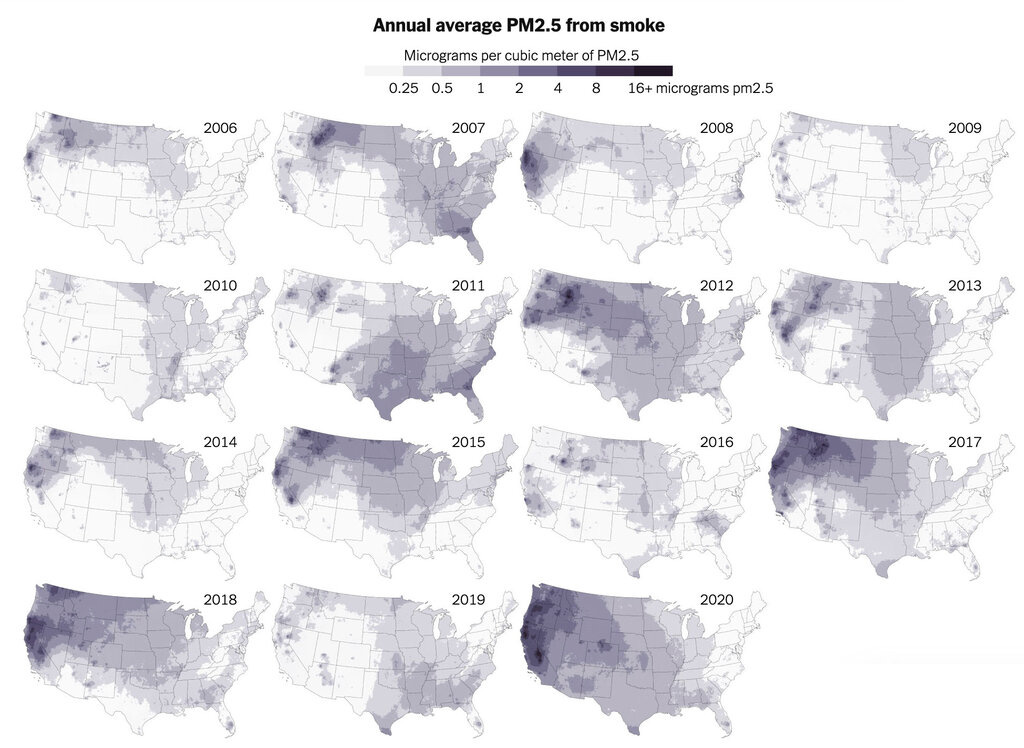

From the New York Times Climate Forward newsletter:

From David Wallace-Wells (also in the Times):

That noise is getting louder as we head deeper into what the fire historian Stephen Pyne calls “the pyrocene.”

“Fire isn’t going away,” Vaillant recently told The Guardian. “We’re going to be burning for this entire century.” The Alberta fires had only just begun to rage, but he saw the course of change quite clearly. “This is a global shift. It’s an epochal shift, and we happen to be alive for it.”

As the capstone to my MES coursework, I wrote a post-apocalyptic novel about life on Earth if we continue to underperform in our response to the challenge of climate change and environmental degradation. It’s a fantasy quest story set in a ruined world with the details grounded in science—not what will happen but what could happen. In the novel, there are two seasons in the Northeast: sere and fungus. Environmental breakdown has reduced lifespans and human stature. Smoke from Midwest wildfires often paints the sky.

I entitled the novel We Once Were Giants. I may launch a serialized version here on Substack, but why wait months to read to the end? In a few weeks I’ll give you information on how to pre-order the whole book.

I think you’ll find We Once Were Giants a compelling—I dare say, entertaining—read. But in life, as in the novel, no one gets to be a spectator at the apocalypse.

Love reading your articles - anna biggs