Man Fails to Plan, Mother Nature Exacts Revenge

Puddock Hill Journal #67: Goodbye to a very old friend.

A Climate Denial Tragedy in Five Acts

Act I

It’s not happening.

Act II

Okay, it’s happening but it’s not our fault.

Act III

Maybe it was our fault, but it’s too late to do anything.

Act IV

There have always been bad storms, anyhow, maybe warming will make the world a better place.

Act V

Uh oh.

A fierce line of storms came through earlier this week. It took down many trees in our area and knocked out power to thousands of folks.

A month before the storm, our patio garden, loaded with perennials, some planted just last fall, looked like this:

Dead center in the background stands a grand red oak, perhaps 100 years old.

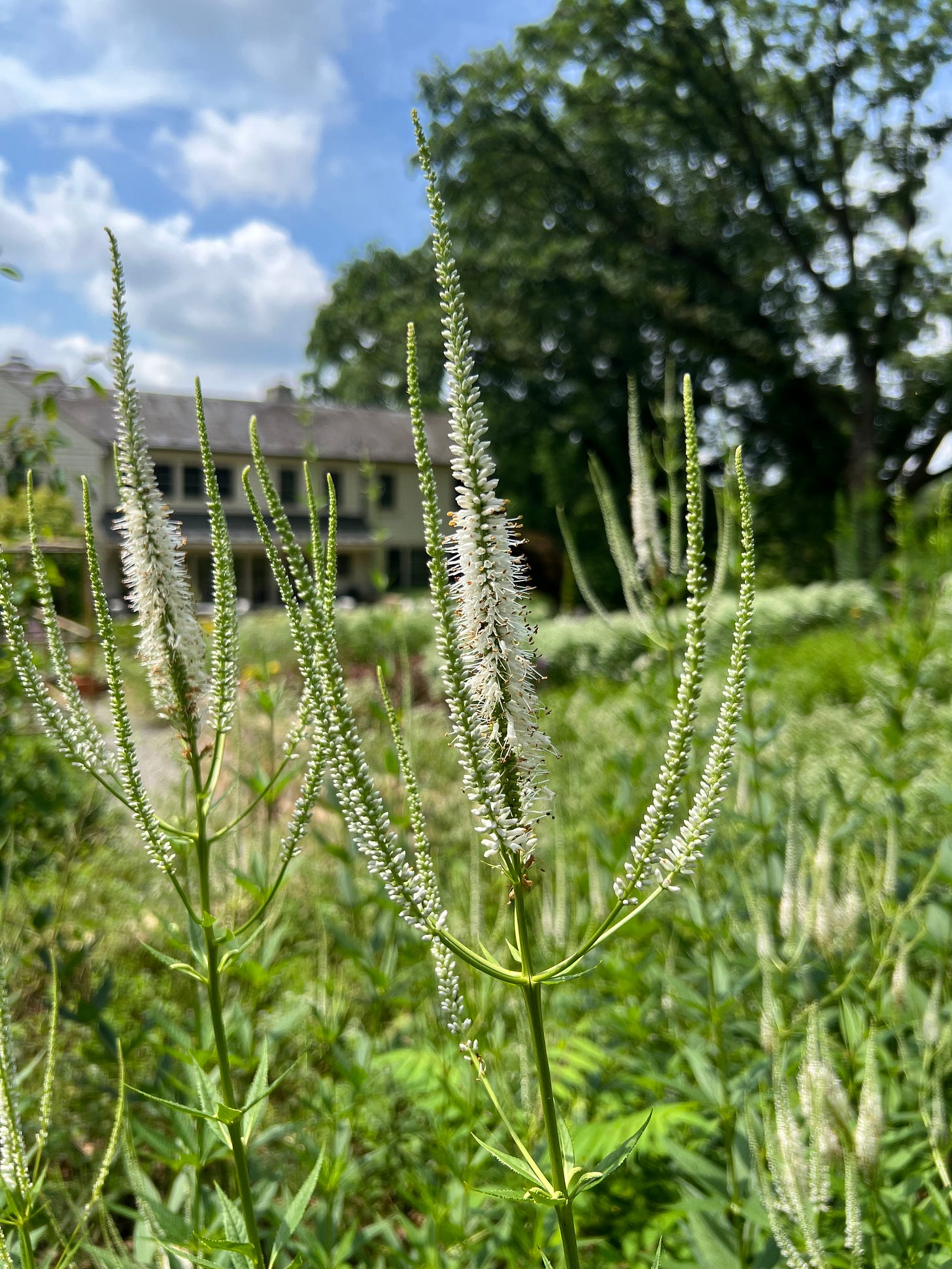

In the intervening few weeks, the blazing star (Liatris spp.) and Culver’s root (Veronicastrum spp.) grew several feet taller and came into bloom:

At around 8:30 the night of the storm, the sky took on an ominous hue—darkness overhead with strange marginal light on the horizon. We were eating dinner in the kitchen and could see, in front of the house, the branches of our old sycamore whipping in violent gusts of wind. There would be no damage to that tree. Sycamores have notoriously hard wood, so much so that they were once used to make buttons, yielding the common name buttonwood.

The red oak would prove to be a different story.

Too many trees seem to be in trouble in this part of the world. Red oaks are vulnerable to sudden die off known as oak wilt disease, caused by the fungus Ceratocysitis facacearum. I have watched several trees die this way, including a spectacular specimen in the right of way along the road.

The red oak in our yard was clearly not in the best of health but did not seem on the verge of imminent death. We were treating it for several pests, and it lost a large limb last year, but by all indications it was doing better. As often happens, however, the strong winds of the storm exposed weakness in the trunk. We heard a huge crash in back and soon learned that the storm had broken this stately tree and destroyed the upper part of our patio garden. In the morning, here’s what it looked like from the lower patio:

A different angle:

During cleanup:

Of course, there have always been storms, in some cases strikingly powerful ones. I can’t say this old oak wouldn’t have died a generation ago just as it went this week, but I suspect climate change made its demise more likely.

Invasive pests have been a problem in North America for decades. The hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), an insect native to East Asia, has decimated whole stands of great native trees throughout the Northeast, including several old specimens by the big pond at Puddock Hill. The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) is wiping out ash trees by the thousands.

The Climate Change Response Framework, a collaborative effort of the USDA Northern Forests Climate Hub and the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science, projects that

Many invasive species, insect pests, and pathogens in the Mid-Atlantic will increase or become more damaging. Changes in climate may allow some nonnative plant species, insect pests, and pathogens to expand their ranges farther north as the climate warms and the growing season increases. The abundance and distribution of some nonnative plant species may be able to increase directly in response to a warmer climate and also indirectly through increased invasion of stressed or disturbed forests. Similarly, forest pests and pathogens are generally able to respond rapidly to changes in climate and also disproportionately damage-stressed ecosystems. Thus, there is high potential for pests and pathogens to interact with other climate-mediated stressors.

What might those stressors be? Heat, for one thing. Like most of the rest of the Northern Hemisphere, we’ve had a record hot summer around here. Warmer winters also make it easier for invasive pests to thrive.

Disrupted precipitation patterns are another factor. The Climate Change Response Framework projects that “Intense precipitation events will continue to become more frequent in the Mid-Atlantic. Heavy precipitation events have increased substantially in number and severity in the across the [sic] Northeast over the last century, and many models agree that this trend will continue over the next century.”

But despite more precipitation falling, there is a likelihood that forest soils will be drier. How can that be?

Longer growing seasons and warmer temperatures would generally be expected to result in greater evapotranspiration losses and lower soil water availability later in the growing season, thereby increasing moisture stress on forests. Further, increases in extreme rain events suggest that greater amounts of precipitation may occur during fewer precipitation events, resulting in longer periods between rainfall.

Humans are driving these changes. EarthWise reports that

Despite the increasing concern about the warming climate, the period between March of last year and March of this year has set a new record for the largest 12-month gain in atmospheric CO2 concentration ever observed. The new level, measured at Hawaii’s Mauna Loa Observatory was nearly 5 parts per million higher than last year’s level reaching more than 426 parts per million.

Associations between increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and climate change are indisputable. While the fossil fuel industry and its enablers refuse to alter the pollution trajectory, the laws of physics persist. Where does that leave the backyard steward? As easily victimized by climate change as the most recalcitrant climate denier.

I have planted hundreds of trees over the past few years, most of which are on their own among the winds of fortune. The falling oak sheared off the limb of a mature maple tree that will never be the same. It crushed nearly the entire upper half of the patio garden—all native pollinators.

There is an old Yiddish expression that translates to the phrase, “Man plans, and God laughs.” I propose a corollary: “Man fails to plan, and Mother Nature exacts her revenge.”

In the great scheme of the world, to decry the loss of a single tree seems like folly. It might have happened without climate change. Yet it might as likely have come about because we’re in Act V of the tragedy we collectively insist on pushing to its terrible conclusion.

Native swamp agrimony (Agrimonia gryposepala) begins to bloom off the hill meadow path:

Native common evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) blooms on the portion of the big pond embankment we didn’t have to mow down for invasives:

Native black cherries awaiting birds:

The big pond on a cloudy day:

It's sad when a loved tree succumbs to a storm. And you're right, climate change is exacerbating conditions for invasives.