In a well-balanced ecosystem, the dead things are nearly as important as the living.

By dead, I don’t mean the seemingly inert geological components, although those are significant, too. I mean once-living things that have expired: animals and plants, of course, but also at times their component parts.

One important theme for the backyard steward is to let go the notion that a neater garden is a better garden. This can be true right beside the house—where, surely, a perfect but sterile paving job would be neater than pesky plants expressing themselves—but it is especially important to keep in mind around the edges of one’s property.

A few years ago, after Kennett Township sponsored a presentation by a Pennsylvania state forester, I invited him to visit Puddock Hill, which some might find significant in scale, but to a state forester represents less than a rounding error. Whether he agreed to come out of generosity or obligation, he showed up as promised a few weeks later.

At the time, I was already beginning to understand that restoring natural habitat in our little corner of the world would require planting many more trees. Not specimens in the middle of the lawn, rather randomly spaced trees planted close enough together that they would grow as trees do in the woods, in light-seeking ways, straight and tall at times, but in some cases crooked and unbalanced. In other words, I wanted woods that appeared to have sprung up of their own accord.

The forester had a look about and approved my plan, such as it was. More important, when I noted that we do not cut down and remove snags in our modest woods, he shared an important data point. A healthy forest, he said, has two and a half dead trees per acre.

If you keep a neat and tidy property and wonder where the woodpeckers at your bird feeder originate, thank neighbors who don’t remove their dead trees. One of the snags by our small pond has stood for several years. Here it is:

Last year, I sat on the nearby bench and saw a pair of pileated woodpeckers (one of our showiest native bird species) working their way up and down a tuliptree that towers nearby. I don’t know exactly where this pair made their home, but woodpeckers are primarily cavity nesters.

Small mammalian critters appreciate dead things, too. Last summer, I was walking along the path through the barn field when a hawk swooped down and grabbed a mouse or vole not ten feet away from the path, both startling and delighting me. If there are no logs or scattered brush in the woods, there are many fewer small critters for the hawks to eat. So, if you enjoy seeing hawks circling overhead and occasionally surveying the landscape from your trees (we’ve never had a nest that I know of), give the little critters somewhere to hide by leaving the downed limb where it fell or at least dragging it to the edge of your property.

Another reason to leave dead trees and limbs on the ground in the woodier spots is soil replenishment. That fallen tree has spent years or decades drawing nutrients from your soil. Hauling it away removes the nutrients, making for less healthy woods over time.

As stewards, we needn’t pursue a policy of complete non-intervention, but we should be aware of our mission to help nature along. At Puddock Hill, we do often settle down fallen trees by breaking up the branches so they don’t stick up too much. At times we also drag fallen tree trunks to areas we’ve only begun reforesting in order to begin establishing proper woodland ecology.

Leaves are another dead thing that we should be more thoughtful about. It is becoming increasingly fashionable to mulch with leaves from one’s property, and with good, sound reasons. Some of the leaves from your trees contain larvae for next year’s insects, which feed next year’s birds and bats.

Last fall, for the first time we blew the leaves from the lawn not only into the woods but also into our planting beds, including those alongside the house. Here’s one of the newer beds we carved out of the lawn last year:

If you Google “leaf mulch,” you will find that most articles advise chopping the leaves. Don’t do it! Chopping kills more larvae, defeating half the purpose. We found that the unchopped dried leaves mostly stayed in place all winter. In spring, we evened them out again with a rake and by hand. On drier spring days, we found that merely walking around could settled them down, a much more natural solution than chopping. Of course, in addition to supporting our insect friends that are so important to the native food chain, this leaf mulch returns nutrients to the soil. And it also does what expensive shredded mulch accomplishes, retaining moisture and suppressing weeds.

So many commercial landscapers have been trained to remove materials from the properties they maintain that it can be a chore convincing them to leave the dead things alone. By explaining why we’re asking them to revise this pattern of removal, we can more easily get them to change their habits.

More important, by redefining our own sense of beauty, we can learn to better appreciate the aesthetic appeal of the woodpecker-attracting snag or the fallen limb.

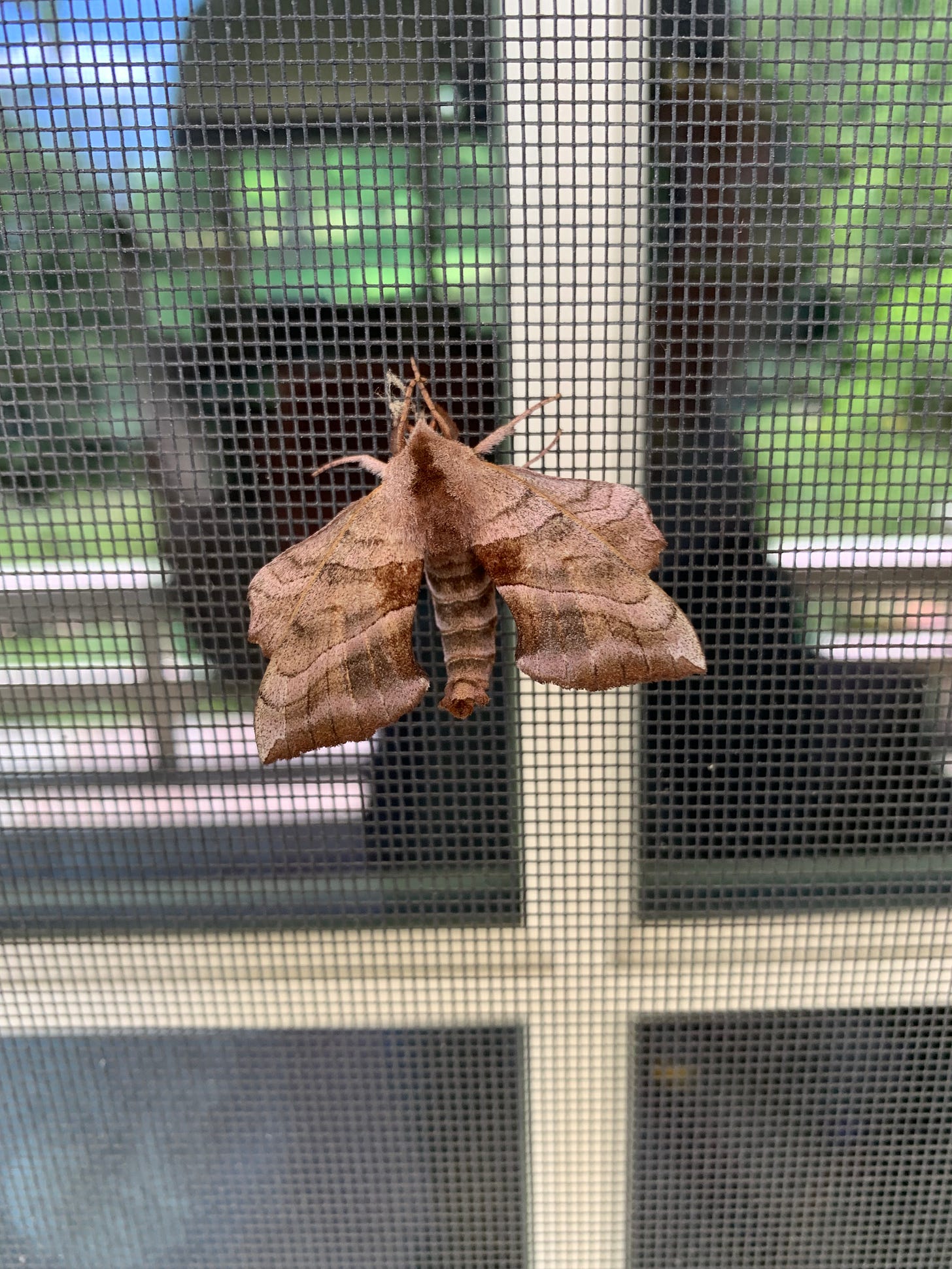

This cool moth came to visit last week. I believe it’s an Achemon sphinx (Eumorpha achemon).

This climbing hydrangea on our arch is lovely but native to Asia. It attracted lots of bees this week:

So did the native Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica):

After a long wait due to supply chain disruptions, we finally finished planting the garden around our refurbished patio. One of the plant species we used is native Foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis), which arrived in bloom. Amazingly, at the same time, and for the first time, I spotted the same plant growing wild in the small pond field: