Defining Success

Puddock Hill Journal #49: Maybe success at backyard stewardship isn’t what I think it is.

For the second week in a row, I asked the landscape maintenance service, armed with mowers and string trimmers, to devote three times the man hours we normally allocate in order to pursue invasive plants, particularly Japanese stiltgrass before it sets seed. We yet need a third round next week.

This will cost us a lot of money, but I view selective interventions such as these as necessary. Necessary, yes, but I wonder whether they are sufficient.

Gardeners of all types set out with a vision. They may inherit a wonderful garden that already pleases them in full, in which case their vision is simple maintenance or a small tweak or two. Or they may begin with a blank landscape and let their imagination run wild.

The backyard steward’s vision comes with specific parameters. While they may vary from one individual to another, in my case these parameters include gardening without chemicals, especially herbicides and insecticides, planting native species most of the time, and encouraging positive natural processes while waging mechanized war against invasives.

My philosophy, simply put, is to support wildlife by encouraging native species and discouraging non-natives, especially those among the latter that can choke off the potential of natives to survive and thrive, thus undermining the local fauna.

When I set out to do this, the goals I established built upon a vision of perfection. The woods on the perimeter would grow tall and strong, I imagined, the soil beneath their limbs covered in decomposing leaves with native forest understory species poking through. Reality: more than half the trees we’ve planted died; some, such as the native beech that took off along the road, may be under threat from new diseases; meanwhile, the trees that are thriving will still take a long time to cast significant shade and drop enough leaves to restore the forest floor, if they ever do.

Vision: native herbaceous species re-establishing themselves along woodland path edges—plants such as Canada lettuce, white avens, deertongue, Virginia knotweed, mayapple, and white snakeroot. Reality: those plants are all present, but invasive Japanese honeysuckle shrubs on the upper big pond path threaten to take over and shade them out.

Vision: meadows where the natives I encouraged—goldenrod, Joe Pye-weed, New York ironweed, milkweed, and dogbane, among others—overtake and choke out invaders like mile-a-minute vine, Japanese stiltgrass, and porcelainberry. Reality: the invasives remain; the Joe Pye-weed, which thrives in a neighbor’s meadow, barely hangs on; patches of porcelainberry and mugwort and Canada thistle and crown vetch continue to assert themselves; and this year, an invasion of Japanese stiltgrass forced us to string trim half the wet meadow to the ground.

Prominent natives seem to come to Puddock Hill in waves. Last year, fleabane flowered everywhere and dogbane grew thick in the wet meadow. This year, those plants appeared in much fewer numbers, but we have an excellent showing of black-eyed Susan and great blue lobelia. Invasive species, on the other hand, never seem to take a year off.

I walk among the trees we planted and will them to grow. Some are already twelve feet tall, but they seem insignificant next to the towering older trees that define a forest. And seemingly every year we lose a big tree or major limb. This one came off an old red oak that’s fighting disease:

It took out an old dwarf spruce (not native) and a native 15-year-old tuliptree. As you can see, we decided to leave the bulk of the limb as a point of interest. I plan to scrape out a shallow bed in front of the log and plant Coreopsis integrifolia ‘Last Dance,’ a late-blooming native cultivar that performed well in Mt. Cuba Center trials.

Then, a part of me thinks: Another bed, another thing we scarcely have time to maintain.

Was my vision unrealistic? If I had (could afford) more maintenance help, would that tip the balance in favor of my ambition?

Earlier this week, I spent a couple hours on the big pond embankment, hitting invasives with my string trimmer. Four or five multiflora rose plants had reemerged in every square yard of earth. Porcelainberry grew thick in places, at times requiring me to mow down, in its midst, native sensitive ferns, deertongue, and herbaceous plants I didn’t have time to identify. In that area, I’m also playing whack-a-mole with common reed, which invades from a neglected wetland on the neighboring property.

This was probably the sixth time we have struck at the invasives in an area that covers about a quarter acre—more or less one percent of Puddock Hill but far from the only spot requiring persistence. It’s quite demoralizing.

Rather than giving in to discouragement, however, perhaps I should celebrate the fact that the sycamore and baldcypress trees we planted in that area have gotten themselves established. One day, they will shade out some of these invasives, making landscape management easier, at least in that spot. But how far off is that day? Two years? Five years? Twenty? I’ll be 81 in twenty years!

So I have begun to ask myself what success looks like. Is it the complete elimination of invasives or at least their reduction to an occasional nuisance? Or is it maintaining the persistence of some natives among the onslaught, giving them a chance to fight another day—perhaps when conditions change in their favor, if they ever will?

Did I mention that, not far from the neighbor’s wetland that has been overtaken by common reed, a beautiful flower popped up on the property for the first time? Upon examination, it proved to be devilishly invasive purple loosestrife. Growing nearby was the ubiquitous stiltgrass we’ve been fighting so hard.

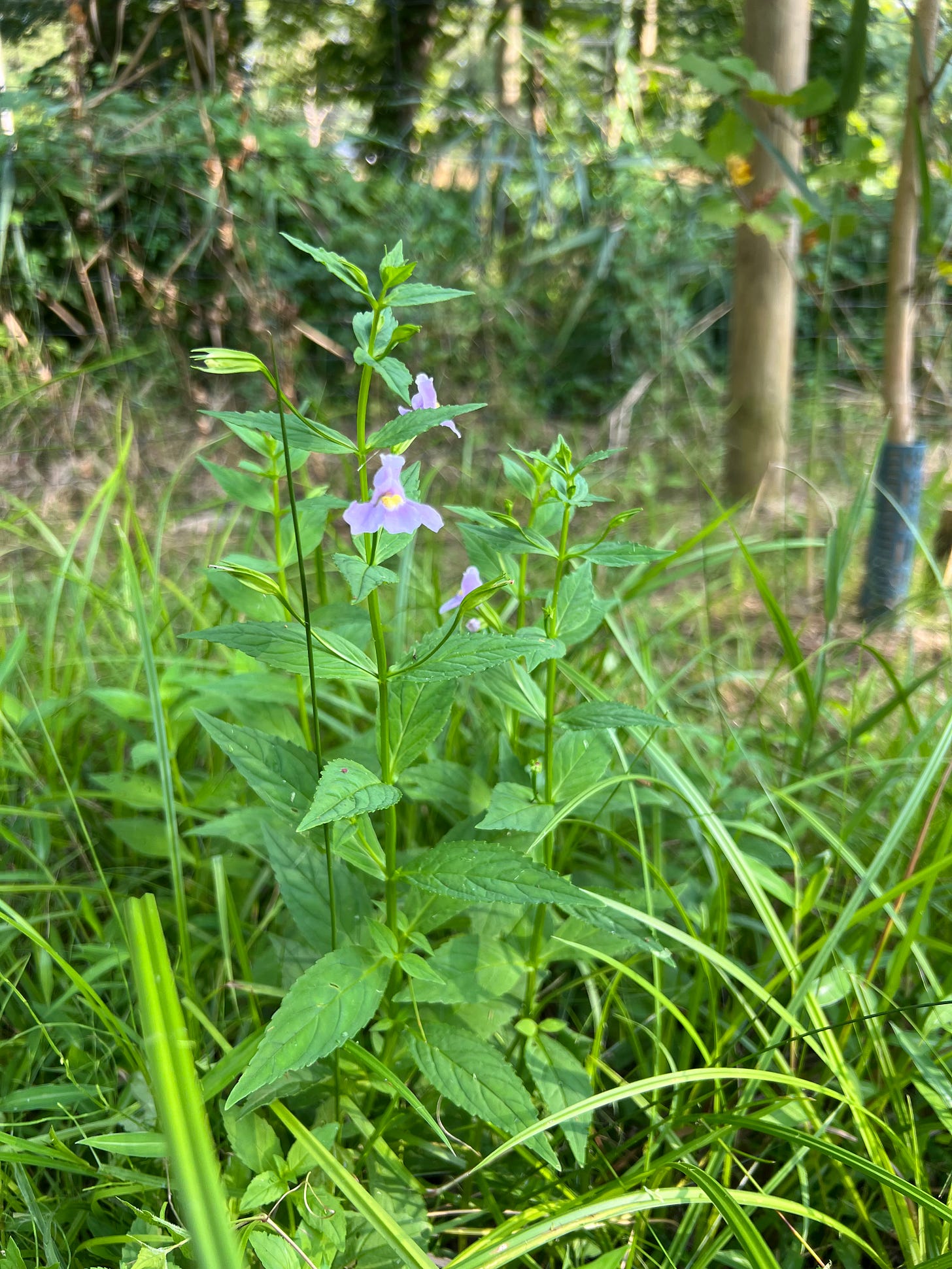

Yet, while string trimming in that area, I also saw a good deal of sensitive fern, Virginia creeper, deertongue grass, New York ironweed, goldenrod, and Carolina horsenettle—all natives. For the first time this year, I spotted this flower and managed to avoid cutting it down:

That’s Allegheny monkeyflower, a stunning native perennial.

Then, for the first time ever at Puddock Hill, I noticed this:

That’s long-leaved groundcherry, suggesting that my efforts to fight back the porcelainberry may—just may—have opened up a niche for this native species. Some years ago, I got ambitious and made chutney with a container of groundcherry fruit I found at the farmer’s market, but in this case I’ll leave the edible ripe fruit (the rest of the plant, even unripe fruit, is poisonous) to fall to the ground, giving it a chance to spread.

I hang on to these glimmers. Maybe they’ll be sufficient after all.

Native hedge false bindweed (Calystegia sepium), sometimes referred to as morning glory, flowers in the barn meadow:

Sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) grows in the woodland edge on the low side of the big pond:

This time of year, I can’t get over the beauty of New York ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis), here on the big pond embankment:

The pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata) we planted in the muck of the big pond this year continues to flower:

Native common evening-primrose (Oenothera biennis) flowers on the big pond embankment:

A single cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), introduced years ago but never wanting to naturalize, blooms by the big pond:

The birds have been working on these American pokeweed (Phytolacca decandra) berries:

Native climbing aster—I think—(Ampelaster carolinianus) wins the race as first to bloom by the big pond: