Backyard Stewardship Is an Act of Radical Hope

There’s a lot to despair over. Plant a tree anyway.

Last year I published a new novel (my tenth!) entitled We Once Were Giants, which—under the guise of a fantasy quest story—envisioned what this nation and world might look like if the reactionaries prevail and we stop efforts to fight climate change and rectify other aspects of environmental pollution. In the novel, people have shorter statures and shorter lives. Everyone carries birth defects, which society spins into a positive by calling them “hallmarks.” Signs of environmental destruction abound.

Cheery stuff, right? But the novel’s hero, Drop Duncan, and other characters have human agency, which means they yet possess the power to make the world a better place. The drama centers around whether the good guys will prevail over the forces of darkness. Thus a fool’s errand unfolds into one hell of an adventure.

In sum, I painted a bleak picture to alert people to the full consequences of our current path while nurturing the hope that we can alter that path before it’s too late—even though, when events in the novel take place, a rational observer might note that it already is too late for Drop to make a difference.

In some circles, this is called whistling past the graveyard.

Psychologists tell us environmental doomism produces despair, and despair is an unproductive emotion. Whether we’re writing novels or just thinking of the challenges before us, pessimism stifles fruitful engagement. This is likely why thought leaders in the environmental space such as scientist Michael Mann and journalist Bill McKibben and communicator Al Gore and data scientist Hannah Ritchie attempt most of the time to emphasize the positive. Hey guys, we can do this!

In my small, less prominent way, I too have attempted to project optimism when writing Backyard Stewardship. My master’s degree in environmental studies concentrated on sustainability because I wanted to pursue solutions. But solutions, I have learned, come slowly. And they come even more slowly when entrenched interests resist them.

Take electric vehicles as an example. There are 2.5 million on the road in the U.S. today, up from near zero a decade ago, and 17 million will be sold worldwide this year. In Norway, EVs constitute 82 percent of new car sales. China has 20 million EVs in the hands of consumers. The technology gets better every year, with prices dropping, range increasing, and charger availability growing. And by many measures EVs offer better technology than internal combustion engines. They’re quieter, less polluting (even without counting greenhouse gases), cheaper to maintain and operate, are usually “refilled” at home…

And yet, one often sees media stories about the shortcomings of EVs, sometimes spun to suggest that plug-in hybrids should be the next step for most people rather than going straight to battery-electric. Gee, could that be because hybrids still burn gas? If you don’t believe oil companies are largely behind this Neo-Luddite narrative, I have a Smith Corona typewriter I’ll swap for your new laptop.

This would all be just a nuisance for those of us who believe in human progress if the delay in implementing solutions for climate change and mitigating other environmental harms weren’t killing us. Consider just a few data points:

McKibben notes that “At the most fundamental level, new figures last week showed that atmospheric levels of the three main greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—reached new all-time highs last year.”

In related news, The Guardian (under the headline “Tenth consecutive monthly heat record alarms and confounds climate scientists”) reports that “Over the past 12 months, average global temperatures have been 1.58C above pre-industrial levels.” Over the threshold we once pledged not to exceed.

The director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies recently suggested that the confounding data noted above “could imply that a warming planet is already fundamentally altering how the climate system operates, much sooner than scientists had anticipated.” In other words, long-feared feedback loops (or “forcings”) could be kicking in. Or, in other other words, the overheating climate may have become a runaway train.

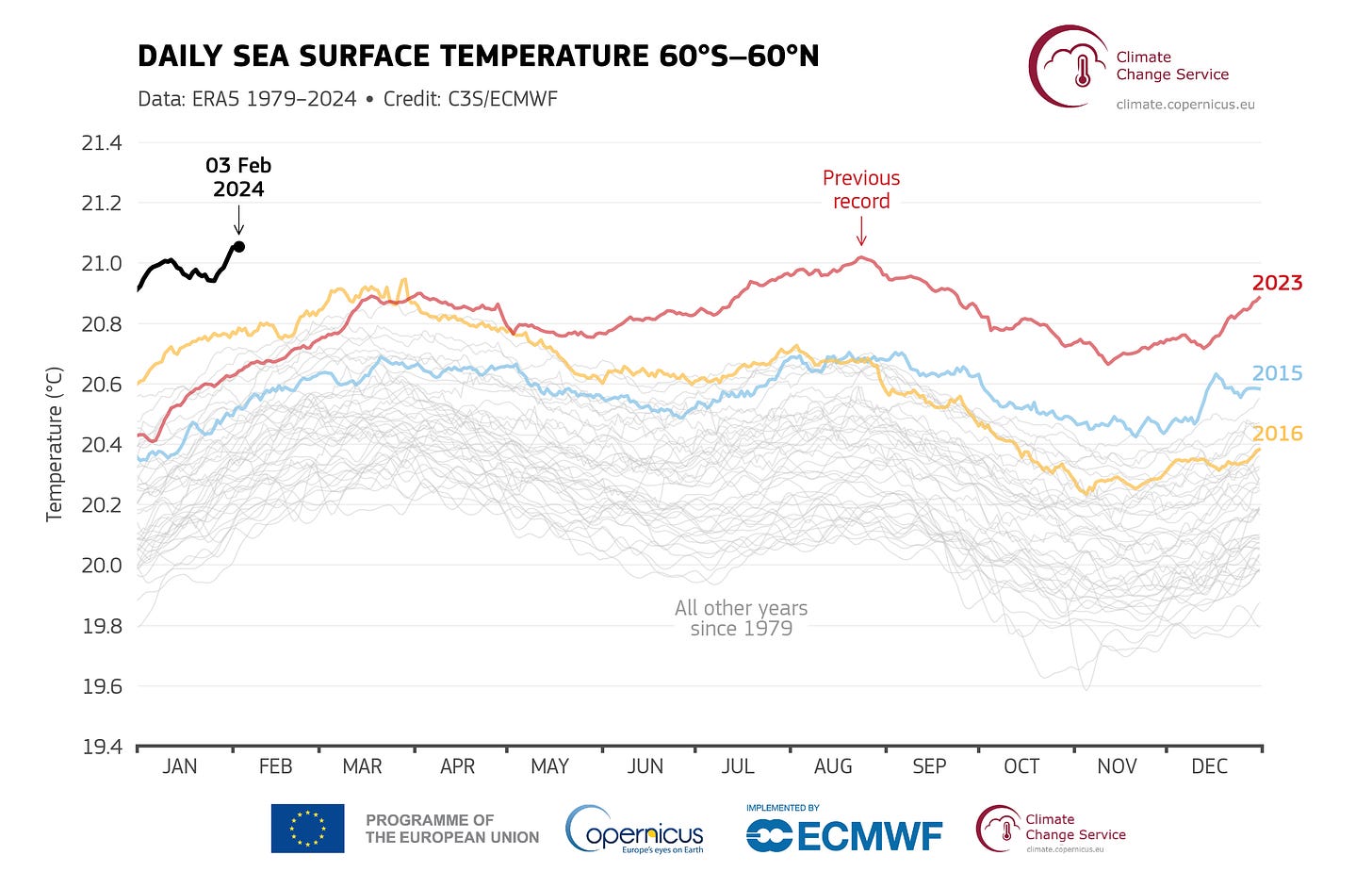

Ocean warming has gone off the charts, too, even considering the effects of El Niño, also shocking climate scientists. This chart doesn’t look promising:

These temperature numbers have dire consequences. During the past Australian summer, the Great Barrier Reef saw its worst coral bleaching on record. Scientists recently documented a 2022 heat wave in East Antarctica that saw temperature anomalies in excess of 30° C. That’s 86° Fahrenheit!

Habitat destruction, another part of the equation for the survival of species, continues nearly unabated. For example, after falling in 2022 by half, rainforest destruction in Columbia rose last year by 40% due to actions by armed criminals. This phenomenon is not unique to Columbia. They’re calling it “narco-deforestation,” and it’s a rising problem even in countries trying to protect natural lands.

A recent study, reported on by the New York Times, found “forever chemical” PFAs in wells and water bodies far from any known source. “This finding ‘sets off alarm bells,’ said Denis O’Carroll, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of New South Wales and one of the authors of the study, which was published on Monday in Nature Geoscience. ‘Not just for PFAS, but also for all the other chemicals that we put out into the environment. We don’t necessarily know their long-term impacts to us or the ecosystem.’” Indeed we don’t know. But we can guess.

I could go on. But if I did, it’s possible I couldn’t go on.

On the “Don’t just stand there, do something” front, McKibben, in a recent Substack newsletter, writes: “We have one force large enough to present any challenge to the rising temperature of the planet, and that is the rise of cheap renewable energy. But it’s not happening fast enough, and to speed it up requires political mobilization to break the power of the fossil fuel industry.”

Personally, although I have strong opinions on public policy, I don’t do political mobilization. As a backyard steward, I do, however, mobilize plants.

Given the bleak facts related above, will backyard stewardship really make a dent? The truth is, I don’t know. Still, like my fictional hero Drop Duncan, people of good will must embark on this fool’s errand. The alternative would truly be unbearable.

As a means of holding the world together, planting a native tree may be insane or, at the very least, an act of radical hope.

Continue the backyard steward’s journey anyway. I plan to.

Goodbye to the desert: