Life is a group effort. I am reminded of that fact whenever I cast my gaze around Puddock Hill.

This time of year, when I sit writing on the front porch on sunny afternoons I see painted turtles gathered by the dozen to bask on the rocks of the big pond.

A stroll down to the small pond reveals hundreds of tadpoles crowding into its shallows. The bigger frogs—their parents!—pop off like strings of firecrackers, croaking, leaping, and disappearing with a splash as I move along.

On Wednesday, I found a chain of frog or toad eggs in the pool of our new patio fountain. I woke up that night plotting how to rescue the tadpoles that will result. (The management welcomes subscribers’ thoughts on exactly whose eggs these are.)

The fecundity of spring and the web of life present challenges for the backyard steward. The landscape we seek to achieve could best be described as organized chaos: relatively tidy toward the house, wild as possible at the edges, and something in between those two strategies elsewhere. Maintenance requires making regular decisions, sometimes daily, about what to encourage and what to remove. And, equally important, how to go about doing so.

This time of year, I occasionally envy those with a tiny patch of garden like the one we had many moons ago in Brooklyn Heights. You pull up a few weeds a week by hand and everything looks great. In contrast, while the scale here at Puddock Hill (16 acres of woods, ponds, lawn, and meadow) offers beautiful vistas, it also presents constant maintenance challenges. The worst of these by far is managing (i.e. KILLING) invasive species. If our war on them is not judicious, however, it will become self-defeating.

Over the past few years, we have worked to gradually eliminate lawn acreage by reducing mowing on slopes and adding planting beds. This year, for the first time, we also embraced No-Mow May, reducing weekly mowing even further—for the moment, at least. In time, if we like the results, No-Mow May could become No-Mow Summer.

Alas, the same ground that supports native and harmless endemic species easily becomes populated by invaders too. And their activities are not self-contained. As in any complex community, the good guys often intermingle with the bad.

Take a look at this picture, which I snapped on the slope above the big pond. What do you see?

I identify at least five plants, and a keener, more experienced eye than mine might spot several more. There’s some kind of grass or sedge (I’m terrible at identifying grasses); Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), which, as the name implies, is a native; some kind of Galium (probably Galium aparine, a native that travels among a number of evocative common names, most notably Stickywilly, although I didn’t touch it to find out); native Jumpseed (Persicaria virginianum); and, just emerging in the center, a noxious vine that somewhat resembles our native grape but usually features lobed leaves—the evil foreign invader Porcelain-berry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata).

Left to its own devices, the Porcelain-berry will come to dominate, alongside (just out of the picture) persistent invaders Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) and Asiatic bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus).

The whole hillside has a similar riot of plants: natives intermingled with invasives. I want to encourage the former and eliminate the latter, but to do so at scale inevitably incurs collateral damage.

There are only a few ways to combat invasive plants that I know of. One could burn them, but that would require a permit, and I don’t want to be the guy who took out the whole neighborhood because an unexpected wind came up. Or one could spray herbicides, but they are indiscriminate, and consequences to the ecosystem are unpredictable at best. Finally, one could undertake physical interdiction: pull them up by the roots, mow them down, string trim them, or cut them by hand.

Although I do carry a pruner when I’m out and about, the problem with hand work is it doesn’t scale; no matter how much time we spend, such efforts amount to a drop in the ocean. Therefore, mowing and string trimming constitute our only realistic options, but these methods inevitably level innocent bystanders.

For example, we’ve had a problem the past few years with a growing infestation of Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) in the meadow by the small pond. This vulgar invader spreads by rhizomes and eventually can crowd out everything in its path, forming a monoculture that resists penetration even by other unwelcome plants. To fight Mugwort this spring, we went to the heart of the matter, mowing it down with the rider where it was thickest and using the string trimmer where it has not yet fully colonized.

Along the way, we undoubtedly took out some friendlies, particularly newly emergent native Goldenrods. Fortunately, these are common on property, but who knows what else we hit. It’s all connected.

Worst of all, we once nearly eliminated a community of Jumpseed that grew in profusion above the big pond. Our native Jumpseed also goes by the name of Virginia knotweed, and in my ignorance I had confused it with highly invasive Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica). (File this under: Dangerous, a little bit of knowledge.) Fortunately, as you can see in the photo above, the Jumpseed remains in the mix.

If we could wave a magic wand and eliminate every invasive plant AND their seed banks, which lurk in the soil for years, we would still wake up next spring to more invaders. Who to blame? Well, the neighbors, of course!

Seeds and berries don’t stay put. The wind carries the seed and the birds transfer the berries. So Puddock Hill can’t fight invasive species alone. We need everyone to do it.

Life is a group effort and so is backyard stewardship.

Some more sights this week.

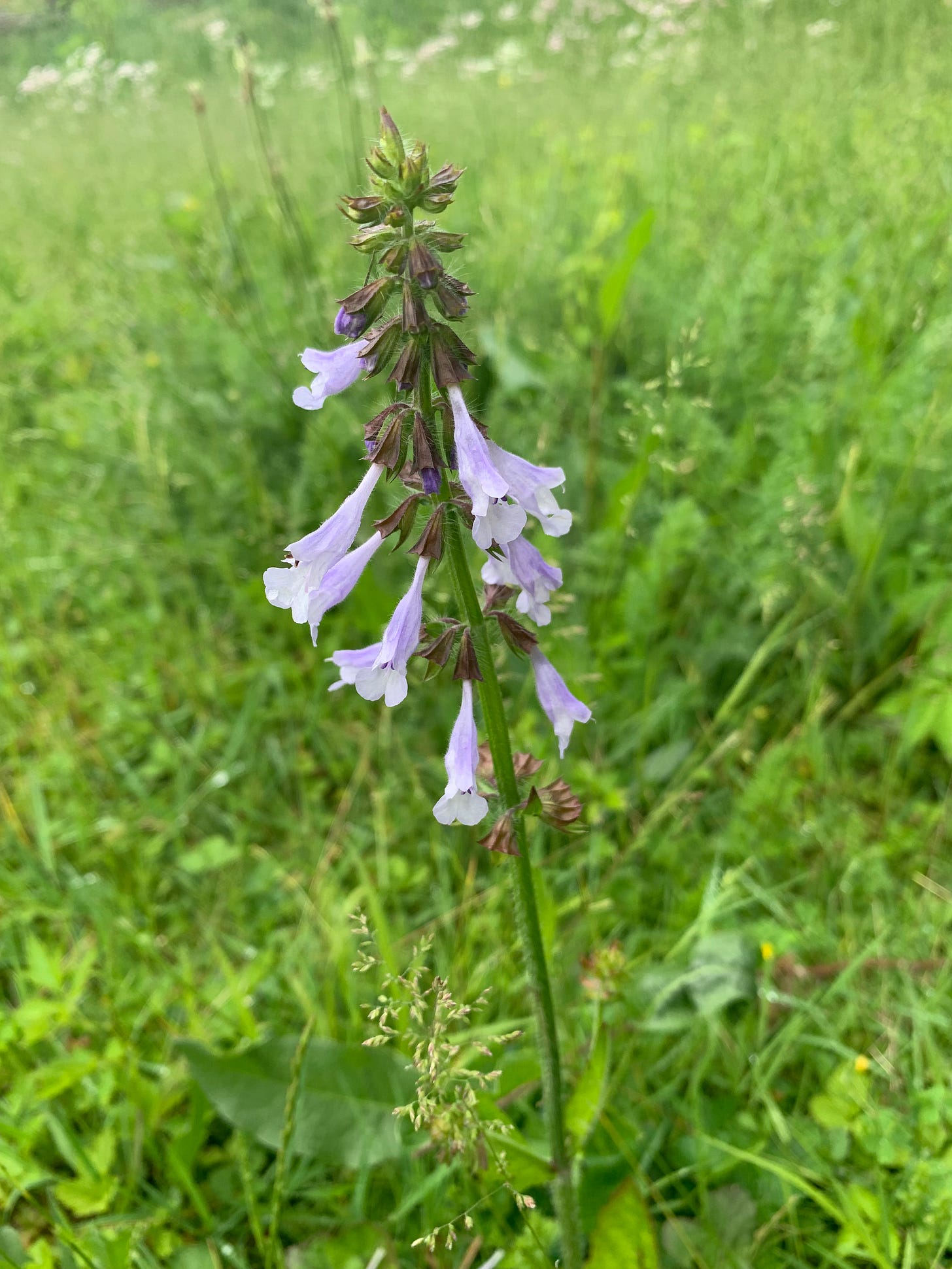

Lyreleaf sage blooms on the big pond dam:

A new walking path delineated by our No-Mow May efforts in what had been lawn:

Older walking paths getting their spring definition. To the barn:

From the barn:

I think this deciduous azalea is native. It’s much happier now that the deer have been banished!